Much to our relief and delight, the bike held true when we left Konglor. Rather than planning our route to follow the main highway 13, the backbone of Laos, Oli had his eye on some rather smaller roads. Our route for the day was road number 1D. Still marked on our map as unpaved and unpassable during the wet season, it is actually brand new, having been completed in 2013. It winds its way through the mountains, twisting and turning past stunning vistas. Although the road was narrow the asphalt was race track quality, and we were loving it.

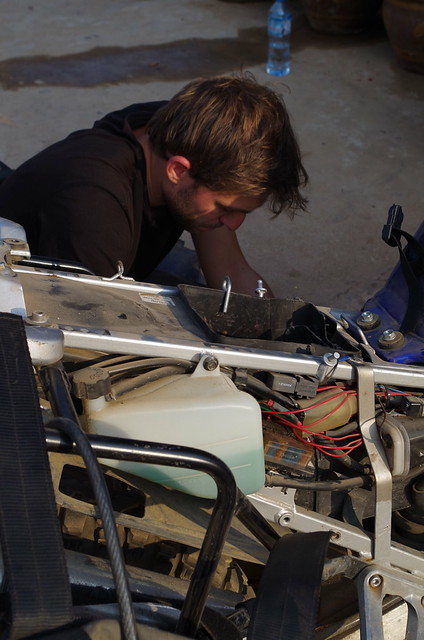

Sadly, as is so often the case with these things, it couldn't last forever. We had started on the newest part of the road, and the last sixty kilometres of our journey were rather more interesting. Although on the whole the tarmac was still good, many sections were peppered with craters. These parts really were inexplicably bad given the age of the road. In one section (see photo below), it had sunk by a good few feet.

Adding to the excitement, the area seems to be plagued by landslides. Looking at the bald, rockless, steep sides of the road this was hardly surprising. We presumed it was mainly an issue during the wet season, as the majority of them looked as if they had been partially cleared away. One however was so bad that the thick dust was difficult to ride through. A truck ahead of us struggled through, its wheels spinning but eventually making it. We followed in its wake, with me deciding to jump off at one point to make it easier to navigate.

As per usual in Laos, there was not much traffic on the road, but what we did encounter made sure we never got bored. Considering the fact that much of the road consisted of blind bends, drivers really do take an astonishing approach to what constitutes the correct side of the road. We are used to it by now, but it is still a little alarming to round a bend and find a large pick up truck in the middle of the narrow road for no good reason.

The award for worst driver of the day however has to go to the operator of a lorry. On the back of his flatbed truck, he was carrying a pile of rocks. These were totally unsecured, and as he wound his way up the hill they would drop off and smash into the road at random intervals. The narrowness of the road, the many bends, and the fact that he kept wandering from right to left made overtaking difficult and dangerous. Thankfully we managed it fairly quickly, but the rocks crashing into the road perhaps went some way to explaining why parts of it are bad considering how new it is!

All this aside, we enjoyed the drive to Phonsavan immensely. We turned up at a random guest house that offered clean rooms, wi-fi and hot showers at a bargain price. It is quite common for hotels in Laos and Cambodia to have a set rules by which the occupier is expected to abide. They usually cover the same topics – no prostitution, drugs, explosives, cooking in your room etc. This one however had a different list, which we thought was brilliant. I presume something may have been lost in translation, but my clear favourite was number ten. This specified that it was forbidden to move furniture around or put up nude pictures...without the permission of the house manager. The idea of somebody not being able to live without their pornographic posters for a single evening, and actually asking if it was okay to put them up was an amusing one. Not having an issue ourselves with any of the rules, we unpacked the bike, stuck our posters on the walls and headed out quickly for a much needed late lunch.

Phonsavan is a small but lively town in Xieng Khouang province. This area is known primarily for two things. The first being the Plain of Jars, and the second for being the most heavily bombed area of Laos during the Vietnam war. With regards to the latter, this really is saying something in the context of one of the most heavily bombed countries in the world. The tragic legacy of this is that unexploded ordnance (UXO) remains a very real risk in Laos.

With this in mind, when we arrived at the Plain of Jars, I drew Oli's attention to the two large signs ahead of us. Provided by the Mines Advisory Group (MAG), it essentially advised that if you stepped outside of the designated areas and were subsequently killed or injured, it wasn't because you hadn't been warned. MAG cleared the area in 2005; 17,390 m2 was sub-surface cleared, and 15,850 m2 was visually cleared only. 26 UXOs were found and destroyed, and 11,770 pieces of scrap. The sign advised that markers had been set out along the path, and that the white sides denoted the areas that had been fully sub-surface cleared. The red sides had been visually cleared only, so stepping off the path was obviously foolish.

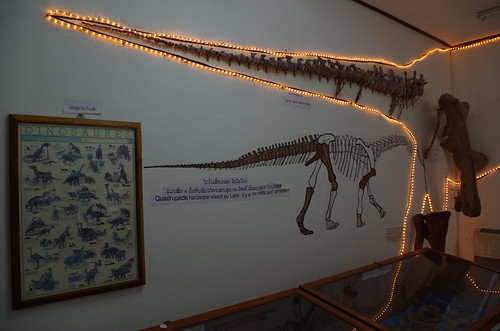

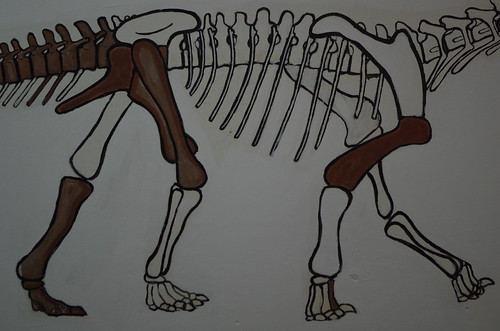

We were at jar site number two, one of over 90 locations at which jars have been found. Nobody knows for sure what the use of these was, although it is widely speculated that they may have functioned as funerary urns, as human remains and gold have been found in some containers. The treasure is obviously long gone, but the jars themselves remain. Most of them are remarkably intact considering that the majority are thought to be over two thousand years old. When the sustained aerial bombardment of the 1960s and 70s is factored in, that they still stand at all is impressive.

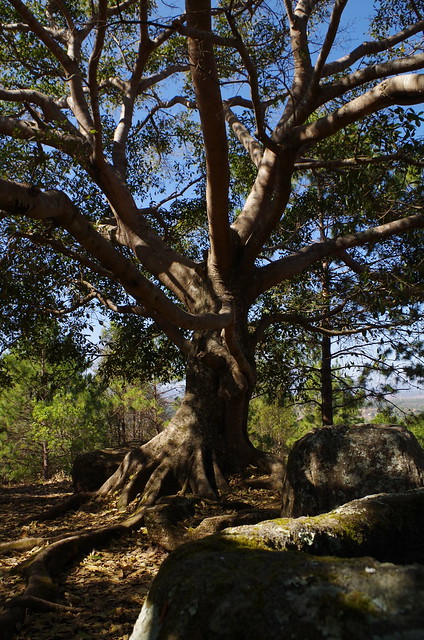

The setting for site two was incredible. The jars themselves are scattered across two hilltops, looking out across the landscape. We took the left path first, quickly finding ourselves at one of the jar clusters. Grouped around a small woodland, we wandered amongst them. We peered inside, but they didn't contain much apart from leaves and occasionally stagnant water, so they were best enjoyed from the outside. There were barely any other tourists around (we would run into just four others whilst at the site), so it was beautifully quiet and atmospheric.

From here, we walked back down the hill, across the track and up to the other point. This cluster was on more open ground with fewer trees, and the views to both sides were astounding. We poked around the jars for a while, before deciding to follow a MAG marked path along the ridge. It was at this point that I realised Oli was sometimes wandering off it. I asked him what he was doing, to which he replied that he thought the general area around the markers had been cleared. I responded by asking him if he had actually read the sign properly. Apparently not. Mistake swiftly corrected, we hiked for a while along the path, but the markers started to run out and we realised there were probably no more jars to find. Nevertheless, it was a beautiful and pleasant walk.

We ate lunch at the lone noodle shop at the entrance, and were pleasantly shocked to find that the food was cheap and amazing. This was definitely not expected at a restaurant squarely aimed at passing tourists. Full and pleased, we hopped back on the bike and set off back down the long rocky track towards the main road. We headed straight through town, and continued out the other side along the No. 7 road. Our aim was to get to a crater field, which was easily reached. At first we could only spot a few holes, but they were still terrifyingly large. However, our eyes quickly got used to noticing them, and suddenly the hillside was littered with them on both sides.

The North of Laos was heavily bombed for two reasons. The first was that it formed a vital part of the supply chain for the Vietcong, in the form of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. As the trail was well hidden by dense foliage, the U.S. approached the problem by bombing a wide area rather than specific targets. The second reason for the extraordinary amount of bombing suffered by Laos was that many of the shells were not actually intended for it at all. They were destined to be dropped on neighbouring Vietnam, but this was not always possible due to weather conditions etc. These unused shells were just emptied out on Laos for no better reason than it happened to be what lay below, which seems horrendously and disturbingly callous. What it must have been like to live with this level of bombardment every day for nine years is both difficult and painful to imagine.

The crater field having given us pause for thought, we got back on the bike and headed back towards Phonsavan. On the outskirts of town we noticed a stupa on the hilltop, which looked brand new. We decided to check it out, and on closer inspection it was not only brand new, but not quite complete. There were no signs, but from talking to locals later we believe it is intended as a memorial to Vietnamese soldiers from the war. Even with the grounds unfinished and bits of building scrap lying around, it was a peaceful and lovely space. We wandered around it for a while, and then continued our way back to town.

We had one further planned stop on our itinerary for the day. Due to the continued impact of unexploded ordnance (UXO) in the area, the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) are heavily involved with trying to improve the situation. They have a visitor centre in Phonsavan, so we were keen to pop in and learn more. The centre was excellent, and provided a good overview of the charity's work in Laos. As well as clearing UXO, they also work with schools and the local population to educate people as to how to minimise risks.

Laos is the most bombed country per capita in the world. Two million tonnes of bombs were dropped, and up to 30% failed to detonate on impact, remaining live and potentially lethal on the ground. Most of the explosives dropped were cluster munitions – large bombs containing lots of smaller bombs, or 'bombies' as they are known locally. Around the size and shape of a tennis ball, they are easily picked up and attractive to play with, so consequently a lot of the casualties are children. The number of these sub-munitions that did not explode on impact is estimated at 80,000,000, a staggering and terrifying figure.

The presence of UXO in the area creates a vicious circle of poverty and underdevelopment. Many accidents occur due to digging, which very understandably makes people afraid to till new land or build facilities. Food scarcity is a problem in heavily contaminated areas, not because there is no land, but because it is not safe to work it. This in turn means more people are compelled to undertake the dangerous activity of collecting war scrap metal, for which they may be paid only $0.20 per kilo. Many people are killed doing this work. By making key land safe, MAG are having a real, positive impact on people's lives. More information is available here. We made a decent donation, and are planning to follow MAG's work in the future.

The next day we were in need of a rest, so planned to do very little other than wandering around and sitting in cafes. We did however make one exception. Two doors down from the MAG office is the UXO Survivors Centre. This charity assists those injured in UXO accidents, and are also doing excellent work and making a difference in affected communities. Rather than simply throwing money at the problem, they work with survivors and their families to enable them to make a living and give them back control of their lives. Survivors are offered training in various skills, and if they choose, a member of their family can make use of this instead. Many of those hurt are subsistence farmers, so their injuries can be even more devastating as it may impact whether or not they can still undertake this activity. In these cases, the work of charities such as these can make a real difference to affected individuals and communities. More information can be found here.

We finished the day off with a walk around town and had a nose around the market. Interestingly, many businesses on the main street have made use of the old bomb shells to decorate their shop fronts. The size of some of these cases was daunting – even if they were not explosives they would still have done a lot of damage when they fell from a height. It was certainly an eye catching style of décor at least. We ate dinner at our favourite haunt, a bar / restaurant serving excellent Lao and Western food, and spent a lot of time talking about what we had learnt whilst in Phonsavan. It had certainly been an eye opener, and the combination of ancient monuments and rather more recent war history was an unusual one. It was definitely worth the visit, and we have realised that we find ourselves a little bit more in love with this country with every day that passes.